Suisun City becomes center stage in California Forever’s city plan.

When California Forever pulled its ambitious East Solano Plan from the November 2024 ballot, many assumed the tech-funded vision for a brand-new city in Solano County was dead—at least for now. The politics were too toxic, the details too murky, and the opposition too organized. But the company didn't retreat. It regrouped.

Now, a year later, California Forever is advancing its city-building ambitions not through the voters of Solano County, but through Suisun City Hall.

In a letter sent April 1 to Suisun's development director, CEO Jan Sramek confirmed the company's willingness to explore annexation into Suisun City—a town of just 4.1 square miles that now finds itself in talks to expand its footprint tenfold.

This isn't a scaled-down version of the plan. It's the same sweeping vision—tens of thousands of homes, jobs, and residents—just rerouted through the standard bureaucratic machinery of California development.

California Forever is a Silicon Valley-backed venture with an audacious goal: build a new city from scratch in southeastern Solano County. Originally operating under the name Flannery Associates, the company purchased more than 50,000 acres of farmland before going public in 2023 with its "East Solano Plan." The idea was to create a walkable, mid-density city—complete with housing for up to 400,000 people, light manufacturing zones, renewable energy infrastructure, and more than 4,000 acres of parks and open space.

California Forever renderings illustrate the vision for the proposed new city.

The project wasn't just about urban design—it was a response to deep structural issues in the region. Solano County, as the company notes, has some of the highest rates of outbound commuting in the Bay Area, with nearly half of its workforce driving to other counties for work each day. The county's median household income is below the regional average, and a third of its residents spend over 30% of their income on housing costs. California Forever framed its plan as a direct counter to these trends: build housing where it's needed, attract jobs where they're missing, and reverse decades of uneven growth.

According to the company's economic forecasts presented by Blue Sky Consulting, the new city could generate $16.1 billion in annual economic activity by 2040 and create 53,000 permanent jobs, while contributing a net fiscal surplus of $41 million annually to local government coffers.

The plan came packaged with promises of affordability, good-paying jobs, and a cleaner, more sustainable urban model. It was pitched as an alternative to both California's housing paralysis and its car-centric sprawl.

Supporters called it visionary. Critics called it vague and premature. A 2024 ballot initiative to approve the project without a full environmental review was met with stiff resistance. Solano County's own fiscal analysis projected massive budget deficits and raised alarms about the lack of enforceable guarantees. Faced with growing opposition, California Forever withdrew the initiative in July 2024 and pledged to pursue a more conventional path. That pivot is now underway.

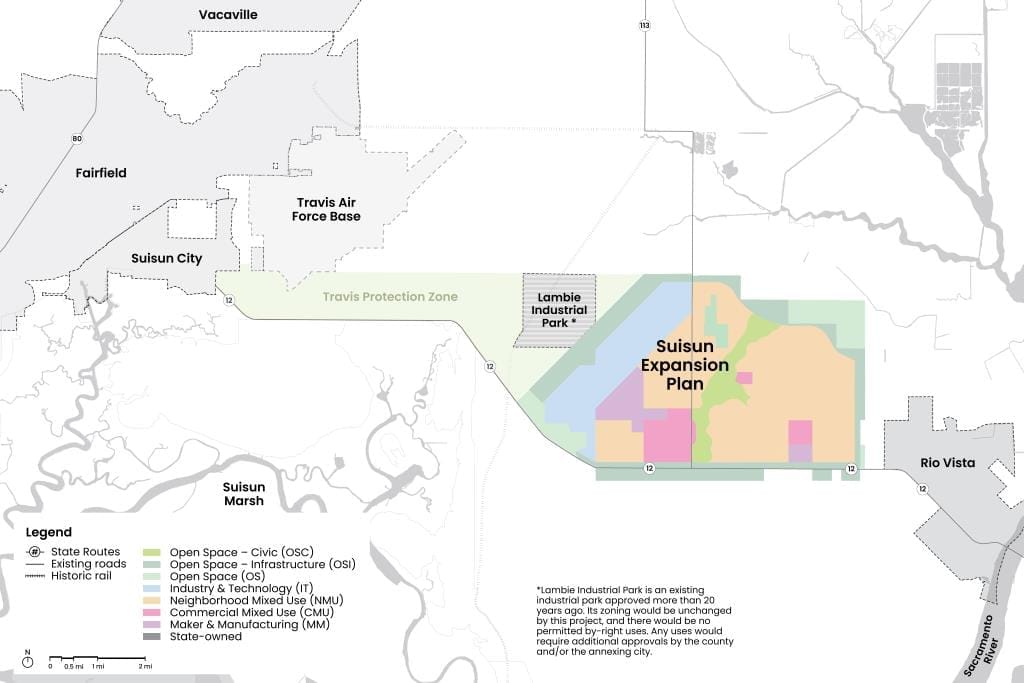

Suisun City and California Forever have inked a formal reimbursement agreement to begin studying the feasibility of annexing 22,873 acres of unincorporated land into the city. The package includes a proposed new residential zone (15,737 acres), an industrial park (1,410 acres), and a "Travis Protection Zone" (5,726 acres) that would serve as a development buffer around the air base.

In exchange for Suisun's cooperation in studying the project, California Forever has agreed to front the cost: an initial $400,000 deposit, a commitment to reimburse all city expenses related to environmental and legal review, and up to $10 million in early public benefits tied to specific milestones—$3.5 million upon EIR certification and a signed development agreement, and $6.5 million following LAFCO annexation approval.

According to the agreement, the money would go toward infrastructure improvements, public safety, park development, and downtown revitalization. In a city with nearly $2 million funding gap between current revenue and long-term needs, the offer is tempting.

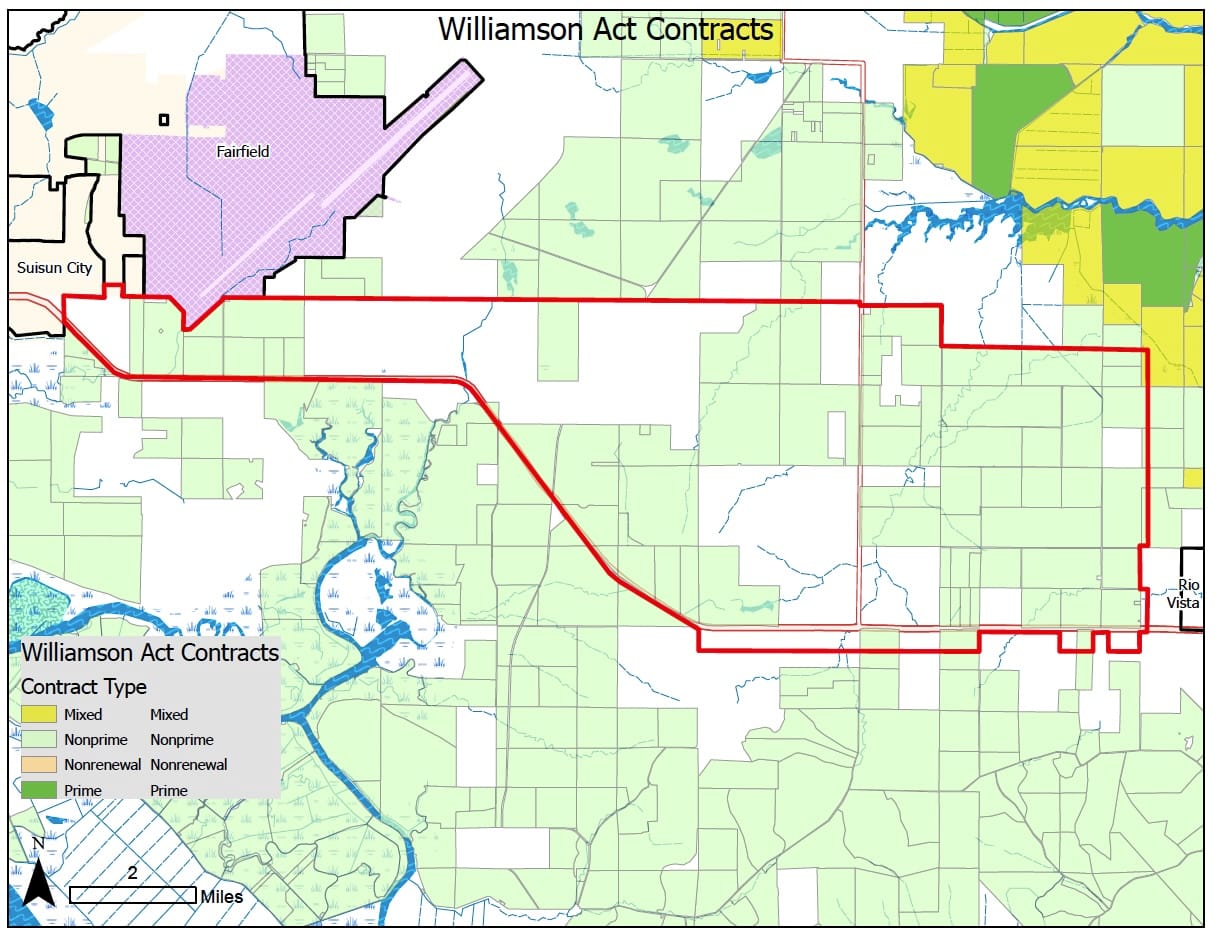

Not everyone is thrilled. Solano County officials, caught off guard by the speed and scale of the Suisun agreement, have urged a pause. In a presentation to the Board of Supervisors on June 24, county staff raised concerns that the annexation proposal could sidestep the county’s General Plan update process. The area under consideration is not currently in Suisun City's sphere of influence and is overwhelmingly zoned for agriculture. Much of it is protected under the Williamson Act or lies within the Travis Reserve Area, intended to safeguard air operations at Travis Air Force Base.

The Board reaffirmed its position: Suisun City should defer any annexation efforts until the county's General Plan update process has fully considered the implications of such a large-scale development. The supervisors emphasized that any decision of this magnitude—one that could fundamentally reshape the county's land use and infrastructure planning—must be vetted through a regional lens.

County officials argue that a project of this scale—potentially increasing Suisun's footprint tenfold and adding up to 150,000 residents by 2048—requires regional scrutiny, not a side deal between a small city and a private developer.

At the June 10 city council meeting, the public got its first real chance to weigh in—and opinions were all over the map.

Some residents expressed deep skepticism, concerned that one-time cash payments could mask long-term costs. "I don't hear the right discussions," one speaker said bluntly. "We're selling property for one-time money, and we still don't know how we're closing our revenue gap."

Others saw opportunity. One longtime resident recalled Suisun's post-industrial decline and said the city had a chance now to "bring back the skills we lost when we lost Mare Island"—a nod to the possibility of new industrial jobs and economic revitalization.

City officials, for their part, have tried to strike a careful tone. The agreement gives them full discretion to approve—or reject—the project at any step. The city will lead the state-mandated environmental review process, and nothing is guaranteed.

The company's pivot away from the ballot was a strategic move. In a joint statement last year, Solano County Supervisor Mitch Mashburn acknowledged that advancing the initiative without a completed Environmental Impact Report had "politicized the entire project" and undermined trust. California Forever CEO Jan Sramek, meanwhile, reaffirmed his commitment to moving quickly. "Delays are not just a statistic," he said. "They have a human cost."

Now, the political theater has been swapped for planning maps. There are no campaign flyers or 10-point pledges. Just traffic studies, legal memos, and a city of 30,000 residents suddenly at the center of a $33 billion idea.

If this process moves forward, Suisun could become the administrative foothold for one of the most ambitious new city projects attempted in California in decades. If not, it will have cashed a few checks, hosted a few hearings, and walked away. Either way, what happens here will be studied, cited, and remembered.