Sacramento region plans for surge in population, 580,000 more by 2050.

Last month, the Sacramento Area Council of Governments released its draft 2025 Blueprint, outlining how the six-county region plans to manage rapid growth over the next 25 years.

Home to 2.6 million people today, the region—which includes Sacramento, Yolo, Placer, El Dorado, Sutter, and Yuba counties—is projected to grow by another 580,000 residents by 2050. That’s roughly equivalent to adding an entire new Sacramento. Total population would top 3.1 million.

The central question facing regional leaders isn’t whether growth will happen—but how to manage it.

The 2025 Blueprint is SACOG’s long-range plan for accommodating that growth while reducing greenhouse gas emissions, improving public health, and curbing sprawl. The plan, updated every four years as required by state and federal law, lays out how the region will add 279,000 homes and 263,000 jobs by midcentury.

SACOG, a joint powers authority governed by elected officials from 28 cities and counties, serves as the federally designated Metropolitan Planning Organization for the region. Its responsibilities include aligning transportation planning with land use goals in ways that meet air quality targets, fulfill housing obligations, and remain fiscally feasible.

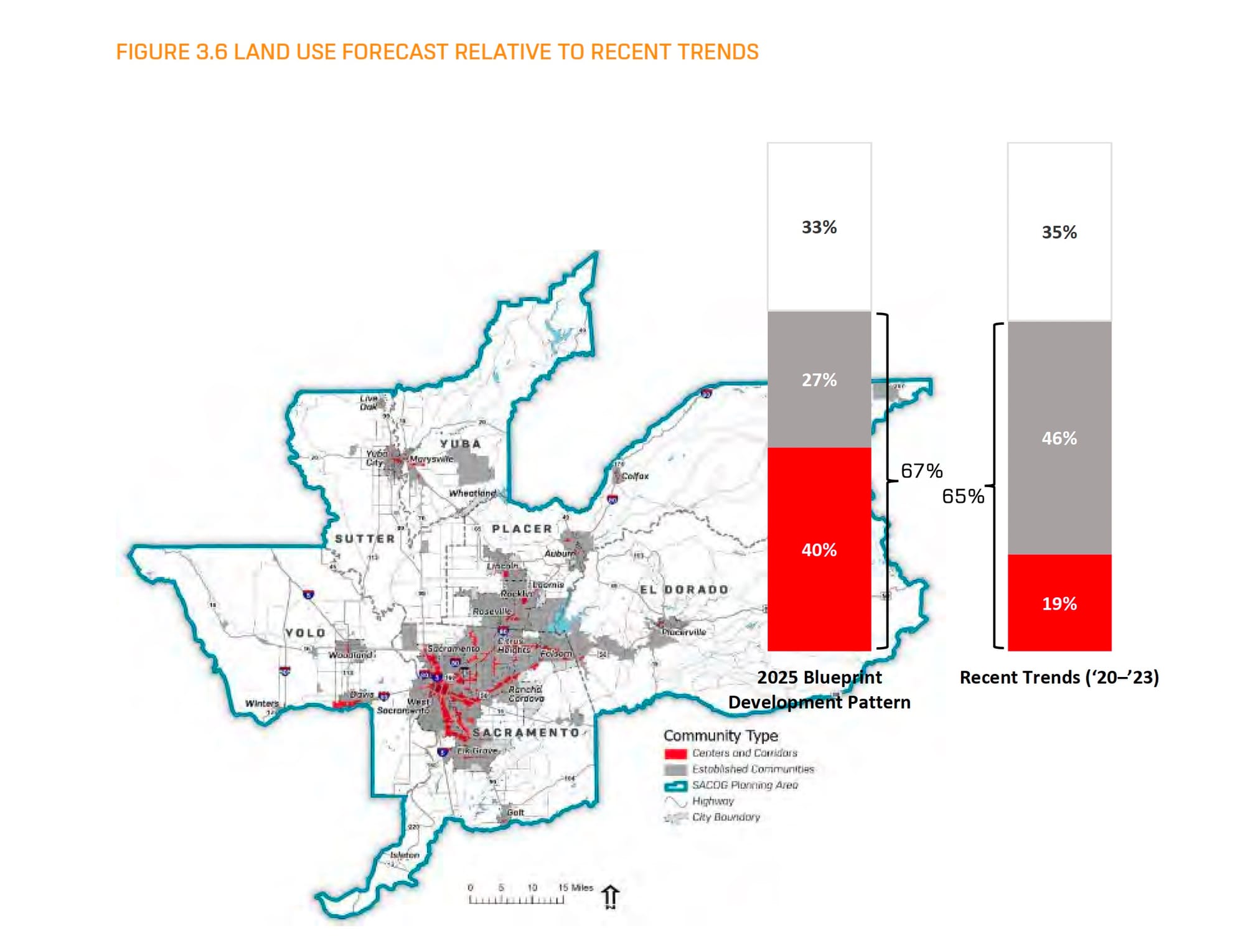

The latest Blueprint takes a sharper turn inward. Rather than pushing new development toward the edges of the region—into farmland or high-risk wildfire zones—it concentrates housing and job growth in existing urban areas and infrastructure-ready corridors.

Between 2020 and 2050, SACOG projects that 67% of new housing and 80% of new jobs will be built within cities, suburbs, and infill zones. The rest will occur in newly developing communities. The approach focuses on rehabilitating aging commercial corridors, building in designated “Green Zones” where utilities already exist, and reducing commute times by placing homes closer to jobs.

The region’s changing demographics add another layer to the challenge. Households are getting smaller, the population is aging, and racial and economic diversity is increasing. Single-person or roommate households now account for 37% of all households. By 2050, one in five residents is expected to be over age 65.

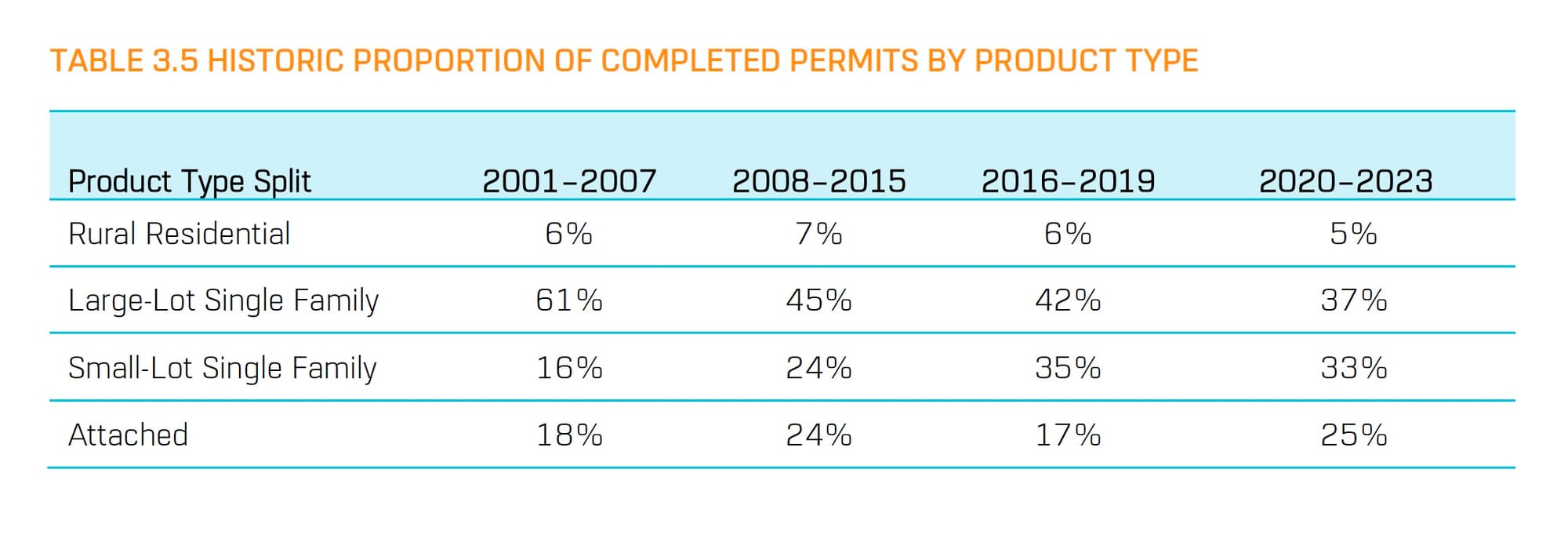

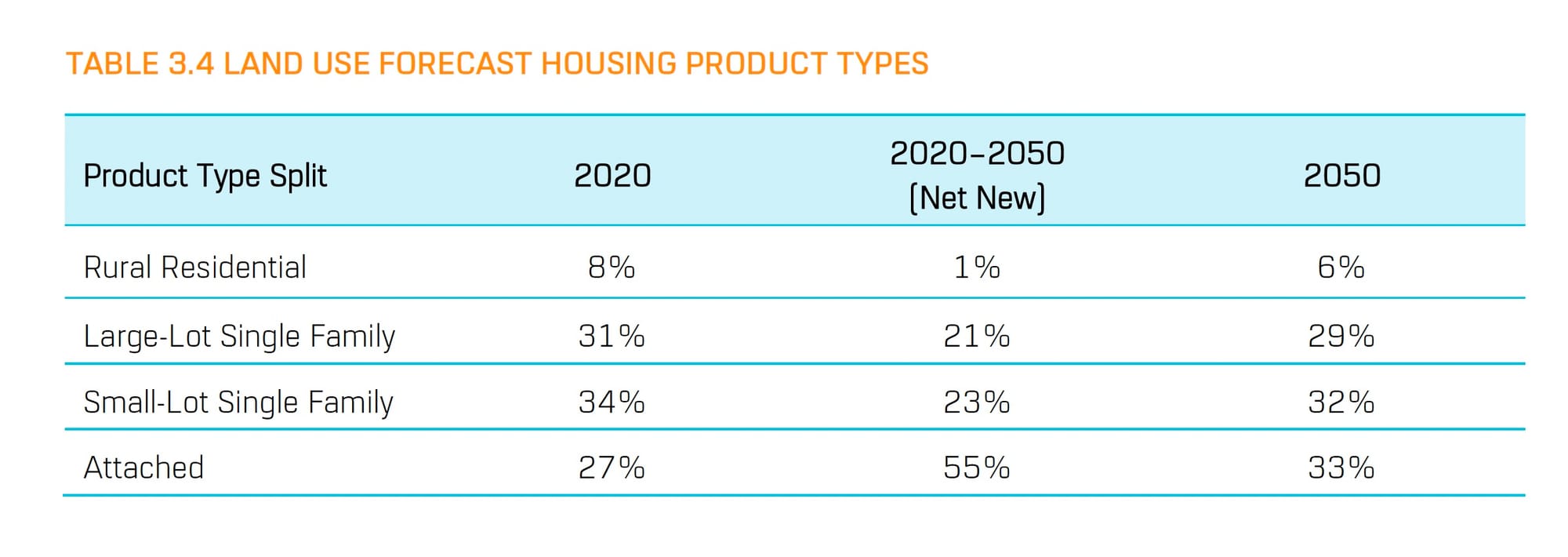

That shift requires a broader mix of housing types. The region’s reliance on traditional single-family homes—61% of new construction between 2001 and 2007—has dropped to 37% today. By 2050, SACOG expects 33% of new housing to come from duplexes, triplexes, townhomes, and mid-sized apartment buildings, often referred to as the “missing middle.” Another 32% would come from small-lot single-family homes.

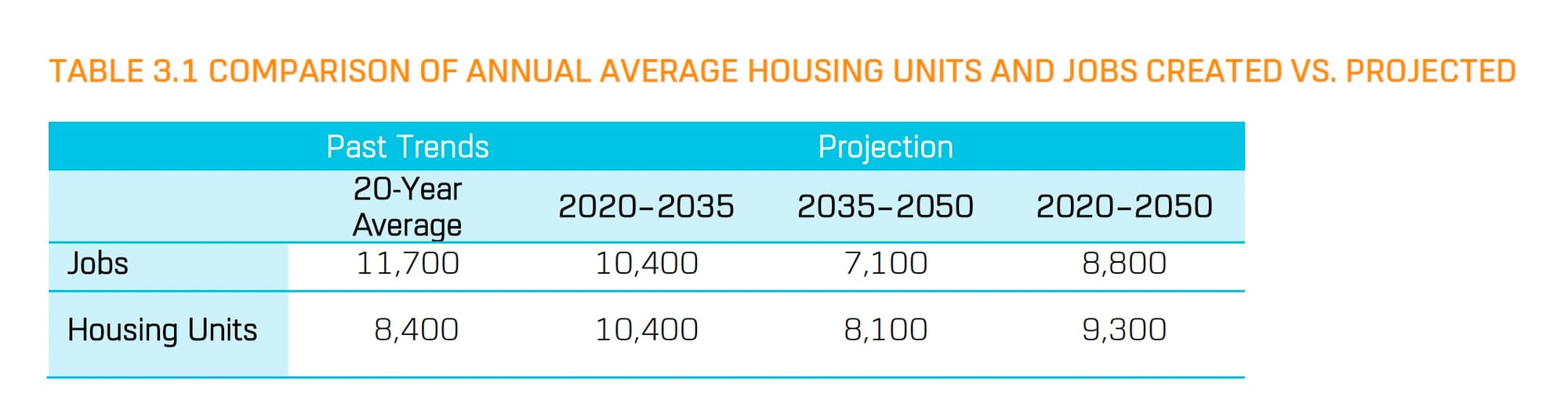

To keep pace, the region would need to build about 9,300 new homes annually—roughly 10% more than the historical average over the past two decades. On the jobs front, employment has grown by an average of 11,700 jobs per year since 2000, a figure roughly in line with the plan’s projection of 10,000 new jobs annually between 2020 and 2035. But SACOG warns that economic volatility, including the 2008 recession and the COVID-19 pandemic, makes long-term forecasting uncertain.

Though government remains a major employer in the capital region, the plan points to growth in “tradable sectors”—industries that export goods or services, such as ag-tech, precision manufacturing, research and development, and business services. These sectors tend to offer higher wages and greater economic mobility. Currently, 38% of residents live in households that don’t earn enough to meet basic living needs.

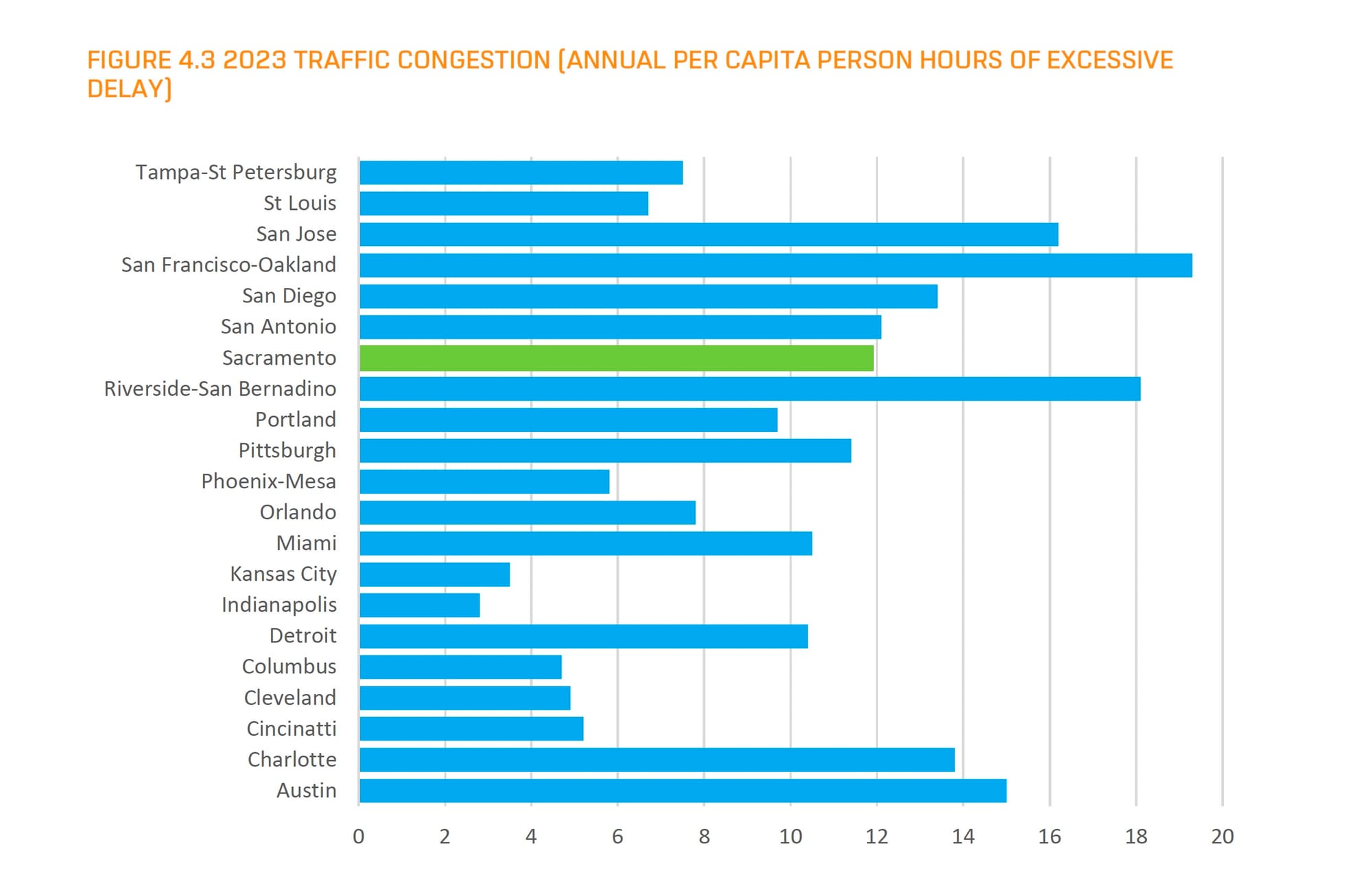

On transportation, the Blueprint calls for investments to lower emissions and ease congestion, even as more people move into the region. Per capita vehicle miles traveled are projected to fall from 17.1 miles in 2020 to 15.8 miles in 2050. But congestion is still expected to worsen without changes to how roads are used and funded. In 2023, Sacramento-area drivers lost more than 12 hours annually to traffic delays—more than in most comparable cities.

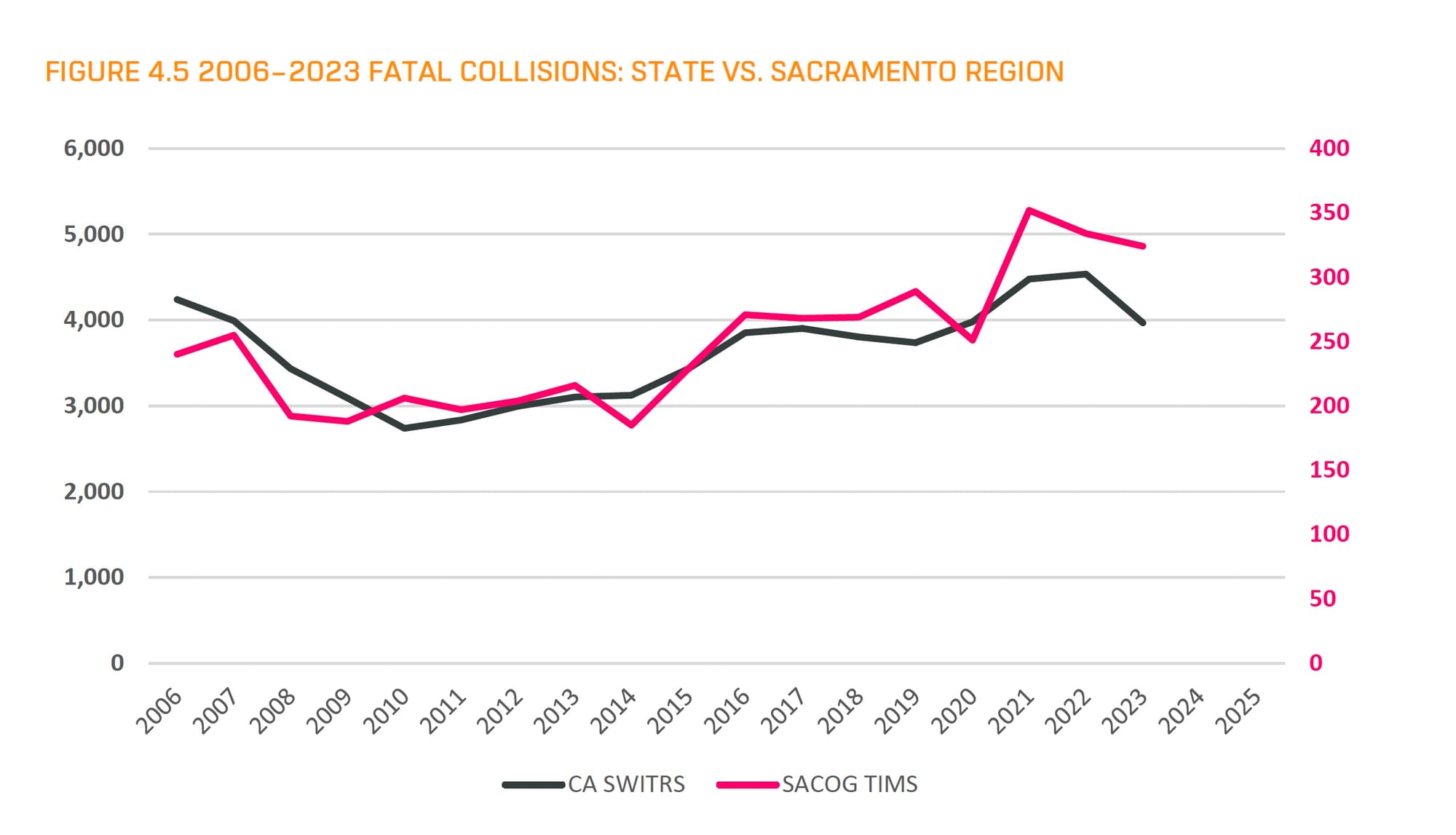

At the same time, the region has seen a rise in serious traffic injuries and fatalities since 2010, particularly in communities with high shares of low-income residents, people of color, and older adults. SACOG reports that serious collisions now exceed the statewide average by nearly 25%.

The Blueprint estimates $41 billion in total transportation investment through 2050, though not all of that funding is secured. Cities and counties nominated nearly $14 billion in road and highway expansion projects, but current revenue forecasts cover only about half that. Local agencies are also falling behind by $400 million to $500 million per year on road maintenance.

Bridge conditions are deteriorating as well. About 60% of the region’s bridge deck area is in poor or fair condition. Without intervention, SACOG estimates the cost to rehabilitate those bridges will climb from $270 million to $341 million over the next decade, with more than 80% of structures likely to degrade further.

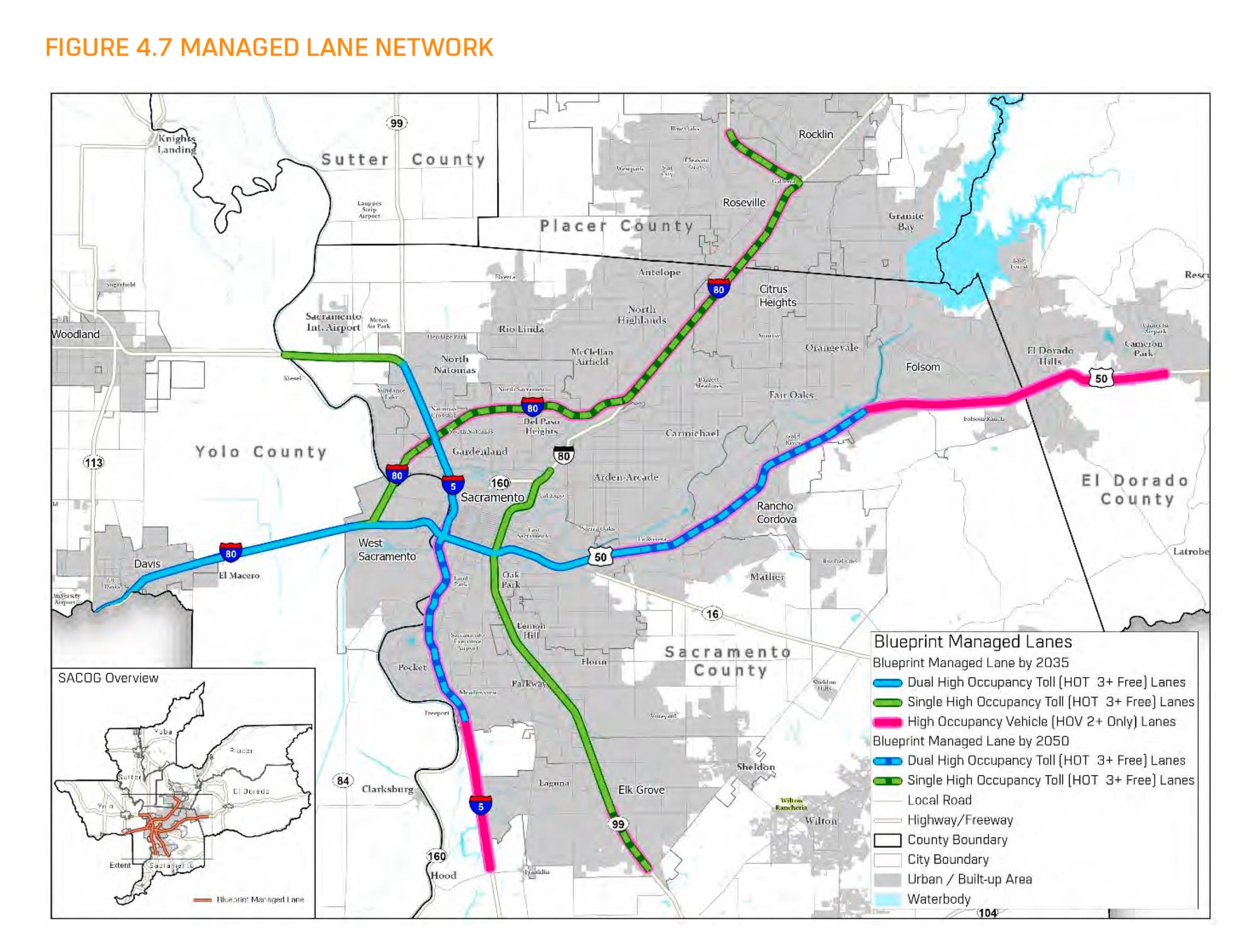

Rather than proposing new freeways, the plan prioritizes upkeep. It earmarks $13 billion to maintain roads and expand options like bike paths, pedestrian networks, and public transit. One major initiative: adding nearly 200 miles of toll-managed lanes on I-5, I-80, and other urban corridors. SACOG projects that pricing those lanes could save users—particularly carpoolers and transit riders—an average of 12 minutes per trip by 2050.

To offset declining gas tax revenue, the Blueprint also explores a mileage-based user fee, though that idea remains in the early stages.

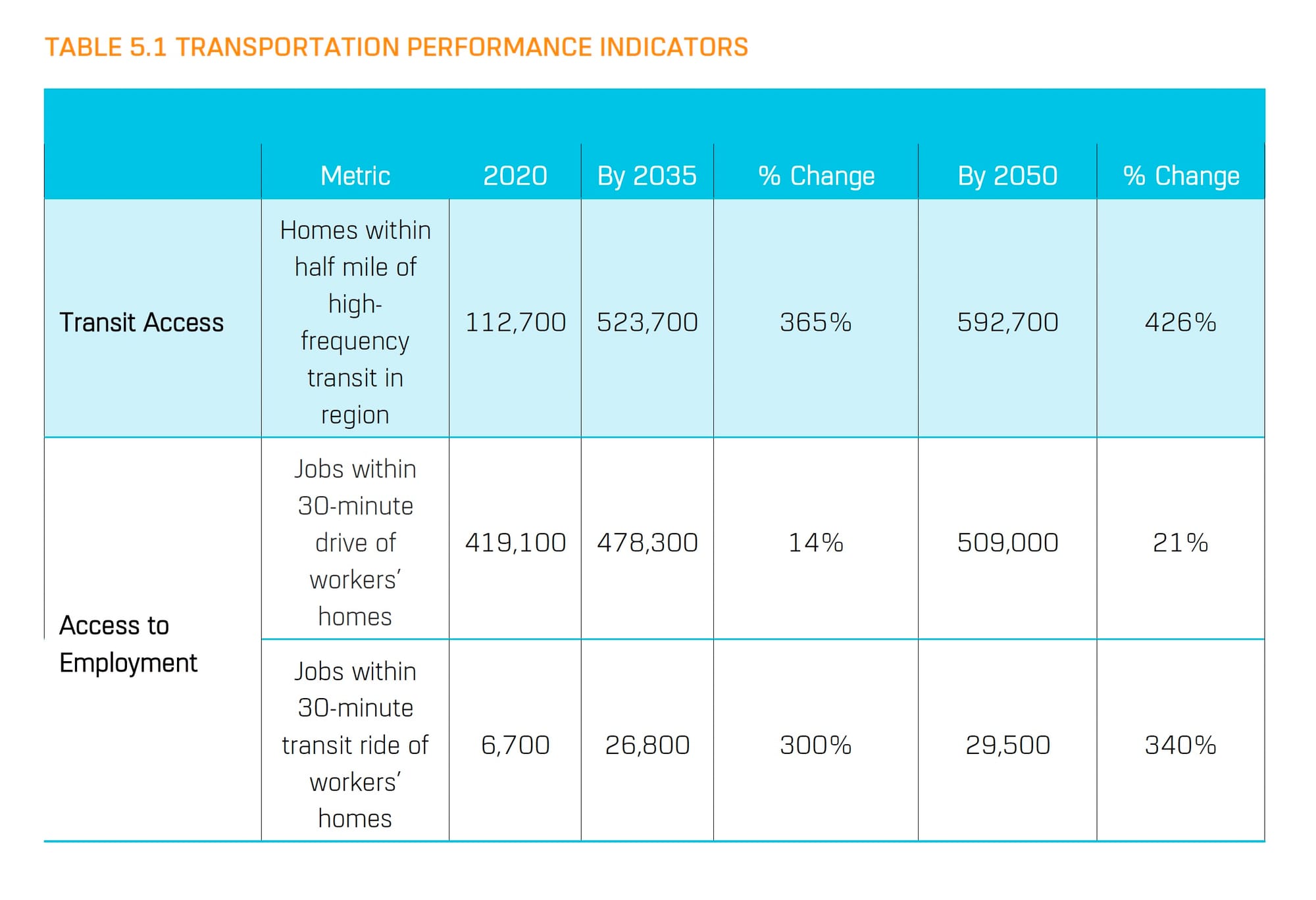

Access to frequent transit service—defined as running every 15 minutes—will more than double by 2040. That shift could connect homes to over 300% more jobs via transit. Still, outreach conducted by SACOG found that most residents rely on driving, with more than half reporting that transit is either unavailable or inconvenient. Among those who drive, 38% said they’d consider switching to transit if stops were closer, 26% cited travel time, and 21% wanted longer hours and more frequent service.

Despite its aims, the plan’s environmental report flags several unavoidable impacts: the loss of farmland, increased exposure to wildfires, air pollution tied to traffic, and pressure on water supplies and public services. SACOG does not have authority to enforce environmental mitigation. That responsibility falls to cities and counties, which decide whether and how to implement the plan.

Public input is still underway. SACOG has conducted focus groups in all six counties, surveyed residents, and visited each city council and board of supervisors to gather feedback.

Residents can comment on the Blueprint and its environmental impact report through Aug. 8. Comments may be sent to blueprint@sacog.org or eircomments@sacog.org. The next public hearing is scheduled for July 31 in Roseville, with full documents available at sacog.org.

What happens next will hinge on that input. The Blueprint offers a vision, but it’s up to local governments, developers, and residents to decide whether the region follows through.