Housing project restarts as Isleton works to recover from fiscal crisis.

Tucked between levees and farmland along the Sacramento River, Isleton is easy to miss. With just over 800 residents and a two-block main street lined with weathered brick buildings and faded neon signs, it is the smallest incorporated city in Sacramento County by both land and population.

Known for its Chinese and Japanese commercial districts—remnants of its early 20th-century immigrant labor roots—the city today feels like a relic: quiet, isolated, and hollowed out.

Tourists passing through may stop for crawfish or a photo of the century-old Bing Kong Tong building, but most drive on, unaware of the fiscal cliff the city has been dancing along for years.

For Isleton, the problem hasn’t been growth—it’s been the lack of it. The city’s population has steadily declined since the 1990s, while rising costs and management failures have gutted its budget and staff. By early 2025, City Hall was open only one day a week. The police department had been dissolved. The public works team consisted of two people responsible for everything from sewer line repairs to leaf pickup.

Then, in June, the Sacramento County Grand Jury issued a blistering report: “On the Brink of Bankruptcy.” It chronicled the city’s failure to adopt timely budgets, its inability to complete audits, and the mismanagement of restricted funds—some of which appear to have vanished entirely. The city council, the report said, failed to govern. It was a damning verdict on a city that had run out of excuses, and nearly out of road.

"The city has been in a financial crisis for some time now," Mayor Iva Walton wrote in an email to Onsite Observer. "Though recently, the depth of it has come to light. The former bloated staff is now at a minimum and the focus for several months has been paying the bills."

But amid the dysfunction, a long-dormant project is coming back to life. The Village on the Delta, a 331-home subdivision originally approved nearly 20 years ago, may now be the best hope Isleton has to reverse its decline. And it’s being led by a developer who sees not just the risk—but the potential.

“This could be my final project,” said Anthony Garcia during a sit-down interview, founder and CEO of Lucas Homes, the Sacramento-based firm that now controls the subdivision. “I could live out here, and just keep churning out houses.”

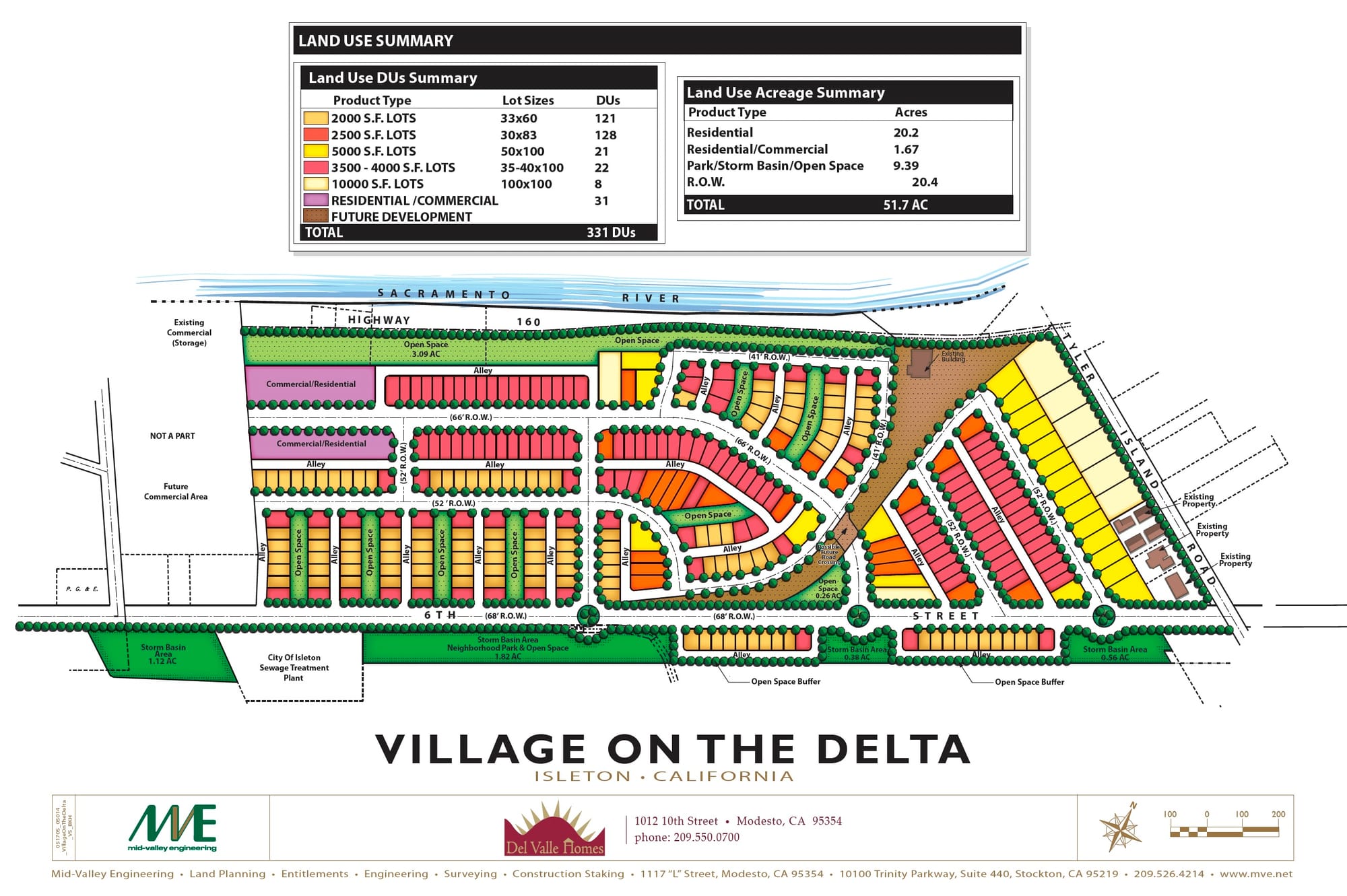

Village on the Delta was meant to transform Isleton. It was planned at a time when the housing market was booming and the town hoped to ride the Delta’s rustic charm into a second act. The 50-acre site is just east of downtown, perched above the floodplain and laid out with sidewalks and narrow lots meant to evoke Craftsman-era neighborhoods. But only 18 homes were partially built before the 2008 financial crisis hit. A legal fight over sewer capacity followed. The developer defaulted, and the lots sat vacant for years.

For over a decade, the subdivision has been a ghost neighborhood—homes half-framed or vandalized, sidewalks leading nowhere. It was not until 2018 that the first set of homes was fully completed—more than a decade after the original plans were approved.

Today, Garcia is in the process of building three new homes, with foundation work already underway and financing in its final stages. The goal is to have all three homes on the market next year. An additional 45 lots are ready for construction, while another two dozen await completion of utility work.

With Lucas Homes now at the helm, the project is moving forward cautiously, with the first round of homes treated as a proof of concept. “The gamble that we’re taking right now is when I build these three houses, am I going to be able to sell them?” Garcia said. “If I can get the prices up to $600,000 or more, then my loans will cover the cost to build.” The most recent highest sale in the subdivision fetched $505,000 back in 2022.

Village on the Delta project site, Isleton — filmed July 16, 2025

The houses themselves are compact two-story models ranging from 2,000 to 2,200 square feet, with 3 to 4 bedrooms, open-concept kitchens, and two-car garages. Lot sizes range from 2,000 square feet to 10,000 square feet. While Garcia considered switching to a more contemporary design, he ultimately leaned back toward the original aesthetic to match the existing homes already built.

Garcia’s optimism comes not just from Isleton’s scenery, but its location. The city lies just 20 miles from the Antioch BART station—near enough, he believes, to appeal to Bay Area workers who’ve been priced out of homeownership but still need to travel to their jobs in the city. For them, Isleton offers a rare combination: a short drive to Antioch, a train ride to Oakland or San Francisco, and the chance to own a home for a fraction of what it would cost closer to the Bay.

As Isleton’s budget teeters and options dwindle, even a modest wave of new homeowners could change the equation. “The development could help the town out tremendously,” said Mayor Walton. “Hopefully in the near future staff and council can work together to encourage future growth in Isleton.”

According to city records and recent public meeting agendas, Isleton faces more than $4 million in long-term debt—a staggering burden for a community of just over 800 residents. In that context, the Village on the Delta is more than just a housing project—it’s one of the few viable paths to solvency.

New homes mean new property tax revenue, developer fees, utility hook-ups, and long-term ratepayers to support water and sewer infrastructure. If the project is built out as planned—with more than 300 homes—it could help close the city’s deficit. The development could also more than double Isleton’s current population—an unprecedented growth for the quiet Delta town.

Garcia estimates that full buildout could take more than 20 years, depending on demand, financing, and infrastructure readiness—but the long-term fiscal impact could be transformative for Isleton.

Many obstacles still lie ahead. The city’s wastewater system is one of them. The Grand Jury report raised serious concerns about how Isleton has handled its utility finances, and Garcia isn’t convinced the infrastructure can support anything beyond what’s already planned. “I’ve been told it has capacity for this [development], but I don’t think it has capacity for any more,” he said.

At City Hall, though, things have been less fraught. Garcia says his dealings with the current council have been productive—more so than with previous administrations. “I’ve always felt that working with the city works better than working against the city. So far, the current council has been good,” he said. “The city wants to see this get built. And honestly, so do I.”

Three new houses won’t change Isleton overnight. But they could mark the start of something bigger. If the Village on the Delta succeeds, it could offer Isleton something it hasn’t had in a long time: momentum.

While the development offers hope, it won’t be enough on its own—Isleton still faces a long road to course-correct a local government that has struggled with inefficiency for years.

Garcia is betting that the quiet river town still has a future. One that starts with rooftops—and maybe ends with a city reborn.